- Home

- Michael Wolff

Burn Rate Page 2

Burn Rate Read online

Page 2

What today’s presenters have in common is that they are considered “content,” as opposed to technology, people. They represent the ideas and concepts and formats that will draw people to this new medium. They will provide the reason ordinary people, not just “early adopters” or technology professionals, will want to make the Internet part of their lives. They represent a notion, too, that Content is King, possessing value that the medium will keep bidding higher and higher prices for. From content will come the hits, the Lucys, the Star Treks, the Seinfelds, of this new medium.

This view of content, with its royal status, is part of the television bias through which most people understand the Internet; a not dissimilar bias, perhaps, to when movies were thought to be a form of theater, and television a form of radio. It’s what I certainly have believed. The Internet is an expanded, heightened, energized form of media, an incredible new mechanism by which to send a coherent message to the world.

“Do you know how bad these ideas are?” whispers my new friend beside me. “Think about this for a second. Games by e-mail. Pathetic! Delusional!”

Candace Carpenter, now taking the podium and hugging Halsey Minor, is another of the Internet’s first generation of programming whizzes (programming in the television, rather than the software, sense). A former executive at QVC, Time Warner, and ABC, her company, iVillage, is one of the best-funded content companies in the Internet business. She has been heralded as the first example of a seasoned media executive crossing over into the Internet space, and iVillage has in fact structured itself as an independent production company, creating shows for network broadcast. Its network is America Online (AOL), which, along with the Silicon Valley venture group Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, has invested more than $12 million in the company. The first “show” produced by iVillage is called Parent Soup—a place, an environment, a channel, for parents on the Internet.

Carpenter, a stylish, blond fifty-something living with her daughter in Manhattan on Park Avenue, is far from the computer company start-up type. She’s very New York, the Californians say. She professes little interest in technology but possesses, as anyone can see, remarkable sales talents and tenacity. She understood that if you wanted to talk to AOL, you had to go to Vienna, Virginia. You had to show up, present yourself, hang around, get people familiar with your face, then wander the halls. It was America’s greatest dysfunctional company, after all. So you had to intervene, confront it.

There’s something appealing, scattered, Annie Hall–like about Carpenter. She plays with her hair and speaks in a tumble of enthusiasms, of contrary impulses, all of them passionate. What the Internet is to her—“This thing, this incredible thing, totally beyond comprehension, totally beyond what anyone would have dreamed up if someone was dreaming of this”—is, well, she can only really relate it to her experience as a recovering alcoholic in AA, to how the whole 12-step dynamic works.

In fact, although iVillage had invested heavily in the creation of traditional magazine and television-like content for Parent Soup, envisioning the product as a cross between a special interest magazine and a targeted cable channel, that approach has now been abandoned. Creating original and traditional content was expensive, and it isn’t what users want, anyway. Users are happier creating their own content. They don’t want to hear the experts, they want to hear themselves. It is just this incredible cacophony of voices, of user-created content, Carpenter says breathlessly. What’s more, the users will do all the work—for free! This, she says, is a viable business model.

It pains me. I am motivated by the opposite impulse—away from the cacophony, looking for the symphony. While I obviously have no quarrel with people getting together to chew the fat in chat rooms across the Internet, it is not a process that I necessarily bring value to.

I am looking forward to Time, Inc., editor in chief Norm Pearlstine’s remarks, because he is likely to represent a voice for journalism—sentences, paragraphs, order, punctuation, point of view—in this new medium.

“You should get Time to buy you,” offers my new friend, as Pearlstine shakes hands with his new media counterparts. “They might as well. They’re going to buy something. They obviously don’t know how to do it themselves.”

“Not impossible, I suppose. We know the people at Time Warner, of course. We were the original consultants on Pathfinder.” (Pathfinder is the multi-million dollar Time Warner Internet site.)

“Something to be proud of,” he laughs.

Pearlstine’s manner at the podium, along with his dark suit and pallid complexion, suggests a higher level of mission and seriousness than that of the other presenters. He seems purposely to eschew the relaxed, casual dress and the bonhomie of the cyber world.

But instead of endorsing the principles of journalistic objectivity and smart analysis and emphasizing the importance of good writing, Pearlstine gives a speech that seems to be about defending and protecting Time. With its bureaus around the world and its journalistic standards, Time stands over here and the riffraff and anarchy of the Internet stands over there. In the end, what will people pay for? What do people always pay for? Consistency, quality, reliability. Sure it’s nice to go to someone’s house for dinner, but you wouldn’t pay for it; it isn’t Le Cirque.

“An industry of metaphors,” interjects my companion.

The real conflict, however, Pearlstine continues, is not between Time and the do-it-yourselfers of the Internet but between Time Warner and Microsoft.

“The truth can now be told,” says my friend.

Microsoft clearly has the capital to compete as a media organization, but does it have the credibility, the integrity, the temperament to function at the forefront of today’s events and popular culture? Pearlstine wants to know.

I am worried about this myself. Anybody who has ever visited the “campus” in Redmond ought to be worried, I am thinking.

On the other hand, a kind of counterintuitive logic says that Time Warner will not be trounced by Microsoft but that both Time Warner and Microsoft will be trounced by some as-yet-unidentified new force. The thinking is that the old, because it is already committed to a direction and a bias and an infrastructure and a set of tools, can never produce the new and that the new will invariably lay waste to the old.

One of the hottest new companies at the conference is Boston-based Firefly. Now its two twenty-something founders follow Pearlstine to the podium. Firefly has been applying various data-matching technologies to musical tastes. For example, a person, X, represented by a digital marker, might indicate an interest in the rock group Jane’s Addiction and theoretical physics and could therefore be matched with Y, a person whose digital marker indicates similar preferences. The goal is to establish enough markers that the system can inform you that you, although you might not know it, are an inevitable Jane’s Addiction fan. Firefly, on the basis of this technology, has succeeded, in its last round of financing, in raising its value to something like $200 million—without yet having recorded any revenues.

While virtually everyone at the conference is devising some strategy to include personalization in what they are doing, I am staying a skeptic.

I believe we are approaching our job in a more personalized way. We have writers and editors performing the old-fashioned task of describing what might be interesting to a reader. I believe the connections between people and their interests are going to have to be made the traditional way—by reviewers, critics, commentators. Software will not be able to tell me if I will like a movie or a rock group or the person who liked the movie or the rock group that I liked.

On the other hand, I feel ill-tempered, crabbed, old. Am I putting an undue emphasis on words and literacy?

I go looking for Norm Pearlstine (in his fifties, he is about the oldest person in the crowd) after the Firefly presentation and catch him during the midafternoon break. I circle first, then double back, observing, moving onto the fringe of his conversation. Pouncing.

Pearlstine looks

at me as I would look at a petitioner. Distractedly. Eyes roving. Moving further away from the vortex of my enthusiasm. It is incumbent on me to suck him in. Hold him. Make the connection. But this is hard to do. He seems glum, distracted, even depressed.

Pearlstine had left the editor’s job at the Wall Street Journal with the notion of building a group of information age media companies based on technology. With investors at the ready, he set out in early 1994 to read business plans and interview technology’s next wave of entrepreneurs. What he had in mind were large databases, corporate systems, business-to-business information models. But he kept getting business plans about the Internet; they surrounded him like flies. It was annoying. For one thing, Pearlstine had never been on the Internet. Nor had anyone he knew been on the Internet. For another, the way the Internet was being described—a free system available to everybody—didn’t make any sense, certainly not to someone who was trying to sell information. It was a relief for Pearlstine when he went to Time Warner, back to real media.

Now, as much as he tried to minimize Time Warner’s new media problem—it wasn’t even a rounding error on their balance sheet, but it was a public relations headache—it kept returning, kept growing. It was Pearlstine’s problem again.

Was it possible that the Internet, an information distribution system maybe as revolutionary as the printing press, could threaten Time’s basic business (remember the way television leveled Life)? Conversely, was it possible that the Internet posed an opportunity that the world’s largest media company, with the best-known information brand names, was ideally positioned to take advantage of? Was it possible that Norm Pearlstine was the man best positioned to lead the information revolution? Or was it likely that Time Warner’s continual losses on its Internet activities would give Pearlstine a big black eye?

“Have the technologists ever run the medium?” I prompt Pearlstine. “If so, not for very long, right? The movie business. What did those guys know about literally making movies? Radio. Television. I don’t see Microsoft really going the distance here.”

“No?”

“Seriously,” I press, “do you think Microsoft is really interested in speaking to America? I mean, who is the messenger here? We’re the messengers. Not those guys, hey?”

“They’re very bright people in Redmond.”

“Oh, I don’t know. Do you really think so?” I scoff. “They’re engineers, marketing people. They’re all from the middle of the country somewhere. They’re not from the East Coast. That doesn’t mean they’re not bright, of course, but it probably means that they’re not, well, media savvy.”

Straining, I lose him. Pearlstine excuses himself with a minimum of politeness, backing away from me and the other entrepreneurs who want Time Warner’s ear.

“I’ve been working the room for you,” says my friend, sliding up beside me in his wheelchair.

“I hope you’re doing better than I’m doing.”

“Buck up. Have you spoken to any of the search engine people?”

Search engines—Yahoo, Infoseek, Alta Vista, and Excite among them—are the software designed to index and catalogue the hundreds of millions of pages of digital information now accessible with a personal computer and a modem (soon enough, it appears, the entirety of man’s recorded knowledge will be reachable with a PC and a modem).

“Infoseek is looking for content.”

“They want it for cheap,” I say bitterly.

“But they want it.”

In the Internet bull market, Infoseek had banked more than $40 million dollars from the unsuspecting public.

Six months before the conference at the Ritz, Robin Johnson, Infoseek’s CEO, and I had sparred over the future of the industry. I argued that given the Internet’s growth—100 new pages of information generated every fifth of a second—and the increasing sophistication of his product’s ability to search out this information, the consumer with an idle query would be dead by surfeit. Enter the word Paris; get back six hundred thousand matches.

What was needed, I said, was discrimination, discernment, point of view, taste.

“Content,” said Johnson.

He argued that content was like oxygen—necessary but plentiful and free. There was a glut, he said. In his analysis of content’s value, it would receive a few modest cents on every dollar received.

Now, those cents sound pretty good to me.

I quicken my pace through the function rooms and halls at the Ritz. I don’t want to lose the opportunity to casually run into Johnson. I move through the lounge looking in back-to-back stuffed chairs, then through the cappuccino bar, and around the palm trees by the pool. Finally, on the cocktail verandah on a precipice overlooking the Pacific I find him huddled with an America Online executive.

If AOL and Microsoft are the superpowers of this industry, then a company like Infoseek is France. A company like mine is an ethnic minority in the Sudan. This is a good way to look at the field of play—alliances, spheres of influence, trading relationships, ideological partners, geopolitical partners (New York versus the Silicon Valley peninsula).

“Robin!” I exclaim with warmth and surprise.

Now I can move in. I can ask to join, presume to join. They will not say go away. They will accept me—dislike me, perhaps, but . . .

“Please. Don’t let me interrupt,” I hear myself say. “I’ll be around. I’m on the red-eye.”

“Okay.” Wan smile from Robin.

I continue on, walking suavely, slowly, gracefully, moving in a physically dignified manner around the cocktail tables on the verandah overlooking the Pacific. I believe for a few seconds that I have accomplished something, that the stars have aligned nicely. This turns quickly into a tumult of regret and indecision. So close, but now what? My main impulse had been to get away and not, as a good salesman would have done, to stay, to press, to insinuate, to worm, to do the unsubtle, the heavy-handed, the uncouth.

“Did you find him? Why are you back so soon? Go back,” orders my friend, doing a wheelie and looking up at me from his chair.

“We’re going to try to meet later.”

“Yeah, sure.”

I shrug.

“Hey, you can do this, you know. You’re nearly a name. The Wall Street Journal writes about you.”

“Twice.”

“Well, you’re my hero.”

“I really hate this part, looking for money.”

“No one has ever gotten rich without begging.”

“I thought that was ‘no one has ever gotten rich without stealing.’ ”

“No. Sucking. No one has ever gotten rich without sucking. This is Silicon Valley. That great sucking sound you hear is the sound of . . .”

The patio, with its several bars and their rows and rows of Perrier and earnest groups of cyber politicians debating the next big thing, was now being transformed around us by the falling light, the musicians tuning their instruments, and the sudden flutter of table cloths. The wardrobe change to light jackets and little black dresses completed the transformation to a swanky soirée.

What was I doing here?

For entrepreneurs (or unemployables) the Internet offered one of the most startling opportunities since—actually, has there been anything to match it? The cost of entry was minimal, the required knowledge base was so idiosyncratic that few could claim a meaningful head start, and there was little or no competition, regulation, or conventional wisdom. It was ground zero: no rules, no religion, no canon, no bullshit. It was start-up time. If all else failed, you could still have the satisfaction of having been there; it was like Hollywood in the teens or Detroit in the twenties. A new American industry was being born.

If you were in the media business—the book business, the magazine business, the television industry, the movies, advertising, newspapers, radio—the Internet offered every opportunity to do it yourself and do it right. You could defy the pace, the shibboleths, the dead wood, and the underlying economic models of those businesses

and produce and distribute content on some altogether new basis.

The Internet was going to be an incredibly sweet revenge.

Because nobody who had a real job got it.

Get in on the ground floor. I could hear the admonition of my immigrant forebears: “You’ve got to get in on the ground floor.”

Cell phones are used at cocktail parties on the West Coast like cigarettes were once used—as a social prop, an excuse to step back for a moment, an opportunity to regroup in a crowd. I use mine to call my wife, who is also my lawyer and my on-again, off-again CFO. She is eager for results.

“Yes, I’ve made some valuable connections, I suppose.”

“Well, anything likely?”

“You have to develop relationships.”

“We don’t have time to develop relationships. We have seven weeks, then we can’t make payroll.”

The tension between us hangs on that date. It was a big surprise for her, I think, to discover that she had married an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurial uncertainties combined with lawyerly precision against the backdrop of already ridiculously pressured lives (and three children) opened up whole new areas of marital sensitivity.

“Yes, I know. It isn’t something that you have to keep telling me.”

“I’m not sure about that. I’m not exactly sure you get it.”

“I get it. What do you think?”

“Sometimes I wonder.”

“I can’t really talk about this now.”

“You can never talk about it.”

“Listen, I’ll see you in the morning.”

I go looking for my friend and wheel him into the banquet hall.

Barry Diller, the former head of Paramount, Fox, and QVC, is due to give the after dinner speech. Diller is a big draw for this crowd. Not only did his “fuck you, I do it my way” countenance make him a kind of patron saint of entrepreneurs, but in many ways the new interpretation of what qualifies as media began with Diller’s acquisition of QVC. QVC provided a model—the transaction model—for the kind of programming that might be effective through computer networks. I once interviewed Diller for the New York Times Magazine, and he threatened me with professional and bodily harm (“I don’t think you understand I would kill you,” he grinned) if I revealed anything about his personal life. But I assumed he had mellowed.

Fire and Fury

Fire and Fury Autumn of the Moguls

Autumn of the Moguls Sefiros Eishi: Chased By War (The Smoke and Mirrors Saga Book 2)

Sefiros Eishi: Chased By War (The Smoke and Mirrors Saga Book 2) Sefiros Eishi: Chased By Flame

Sefiros Eishi: Chased By Flame Chased By War

Chased By War Chased By Flame

Chased By Flame Burn Rate

Burn Rate The Man Who Owns the News: Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch

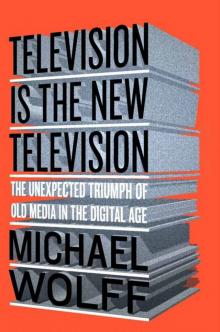

The Man Who Owns the News: Inside the Secret World of Rupert Murdoch Television Is the New Television

Television Is the New Television